In my last post, about how the law might evolve (devolve?) under a Trump presidency, I forgot to mention the promise that inspired it: Mr. Trump’s pledge to reform libel law:

I’m going to open up our libel laws so when they write purposely negative and horrible and false articles, we can sue them and win lots of money. We’re going to open up those libel laws. So when The New York Times writes a hit piece which is a total disgrace or when The Washington Post, which is there for other reasons, writes a hit piece, we can sue them and win money instead of having no chance of winning because they’re totally protected.

I assume that he is talking about the so-called Sullivan defence, although whether he is aware of that is another matter. New York Times v. Sullivan concerns an ad placed in the paper by four African-American pastors from Montgomery, Alabama, under the signature of 64 prominent supporters, including Harry Belafonte, Nat King Cole, and Sidney Poitier. The ad, which appeared on March 29, 1960, alleged that civil rights protesters of the day had been “met by an unprecedented wave of terror by those who would deny and negate that document [the U.S. constitution] which the whole world looks upon as setting the pattern for modern freedom.” Among other things, it sought funding for the defence of Martin Luther King, Jr., whom it claimed Montgomery police were persecuting, illegally.

New York Times v. Sullivan concerns an ad placed in the paper by four African-American pastors from Montgomery, Alabama, under the signature of 64 prominent supporters, including Harry Belafonte, Nat King Cole, and Sidney Poitier. The ad, which appeared on March 29, 1960, alleged that civil rights protesters of the day had been “met by an unprecedented wave of terror by those who would deny and negate that document [the U.S. constitution] which the whole world looks upon as setting the pattern for modern freedom.” Among other things, it sought funding for the defence of Martin Luther King, Jr., whom it claimed Montgomery police were persecuting, illegally.

The ad did not name Sullivan, a Montgomery commissioner, but he sued on the argument that he was accused by innuendo. While there were inaccuracies in the ad, the U.S. Supreme Court held that (as the headnote to the case puts it) a public official could not succeed in an action “for defamatory falsehood relating to his official conduct unless he proves actual malice – that the statement was made with knowledge of its falsity or with reckless disregard of whether it was true or false.” In later cases (see, e.g., Curtis Publishing Co. v. Butts, 388 U.S. 130 (1967)), the rule was extended to include public figures generally, notoriously, Jerry Falwell in his lawsuit against Hustler magazine (485 U.S. 46 (1988); see my Ardor in the Court: Sex and the Law, pp. 246-47, 251).

Note that if the impugned words are “purposely negative and horrible and false,” or “a hit piece that is a total disgrace,” no reform of U.S. libel law is needed: such “articles” would exhibit actual malice. The defendant in such a case is not “really protected.” (For somebody who is in court so much, you’d think Mr. Trump would know this.)

The barriers to striking down Sullivan are not insurmountable, however, although they include formidable and consistent precedent in the U.S. regarding free expression. In Falwell, for example, in his judgment for the court, the very conservative Chief Justice, William Rehnquist, ruled against the reverend, never mind some really foul if deliberately absurd allegations about his supposed sexual conduct with his mother. (The piece in issue was a parody of advertising about “My First Time” drinking Campari liqueur.) The article was disgusting (to many of us, anyway), but was not created with actual malice.

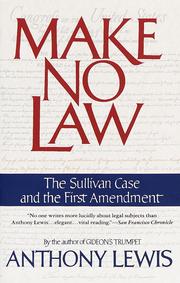

For more detail on Sullivan see Anthony Lewis, Make No Law: The Sullivan Case and the First Amendment, Random House, 1991.

**If you’d like to be notified of each new posting, let me know via the “contact” page and I’ll put you on my e-mail list.**