(Parts of this essay originally appeared in my column in The Lawyers Weekly)

Colloquialisms in a legal context can give the translator at least as much trouble as legalese. In 2001 I was called upon to translate some material dealing with trademark infringement and the famous remark by Justice Foster of the English Court of Chancery: “Only a moron in a hurry would be misled” so as to confuse a tabloid called the Daily Star – featuring lurid sex scandals, murders, and topless crumpets on page three – with the Morning Star published by the plaintiff.(1) The Morning Star was a communist political tract and had recently changed its name from the more notorious Daily Worker. As the translation involved a general discussion of this unattractive arriviste among legal fictions, I was obliged to render not only “a moron in a hurry” into credible legal French, but also “a moron in a hurry in a dimly-lighted room,” in homage to our dim-witted hero’s later appearance in a forgery prosecution. When the defence there said that only a moron in a hurry would have been fooled by the forgery, the Crown asked, “Yes, but what about a moron in a hurry in a dimly-lighted room?”

How to proceed as translator? Well, you review the French you know for “moron.” You don’t want the clinical sense, because what Justice Foster means is not really “moron,” psychometrically, or “idiot,” or even “fool,” but something more like “numbskull,” “scatterbrain.” I had a Frenchism in mind which I particularly like, but I looked in my dictionaries to make sure. I got another technical term: crétin.

I tried an old translation program I once bought on a lark, and that’s really all it’s good for. It gave me idiot for “moron,” and for his sojourn in the finster, “Un idiot à la hâte dans une [dimly-lighted] salle.” This wasn’t bad really, but it just couldn’t handle “dimly-lighted.” In fact, the much-more modern Altavista translation utility on the Internet did worse: un moron dans une hâte dans faible–allumée une salle. Never mind the word choice, even the word order and grammar were wrong. And when I asked it to translate back un moron dans une hâte it gave me “a moron in a haste.”

The Web’s WorldLingo (note that this was 2001) at least got the word order: un moron dans une hâte dans une salle faible-allumée. But I turned back to my own translation, confident that no machine could come close to replacing subtle little me. And I went with my first choice: “un con pressé” en sortant à la hâte d’une salle faiblement illuminée.

The machines had missed the point that “moron in a hurry” needed quotation marks to show the irony. They had missed the idea that he was rushing through (en sortant de) the room, and that the room wasn’t made weak with light but lighted dimly (not faible, the adjective, but faiblement, the adverb). But it must be said that, at least on the evidence of this small test, Google Translate has advanced machine translation. When, in mid-2013 I fed it our moron in the finster, it immediately regurgitated, “un crétin pressé dans une pièce faiblement éclairée.” While this human translator believes that crétin remains inexact (in a sense, too colloquial and slangy), the adverb problem was solved, and arguably éclairée is better than illuminée, although mal éclairée might be better French than either.

Best of all, I got to use the colloquial con, a term francophones reserve for real twits – someone who, according to my British-French dictionary (which I use partly because it makes life even more interesting), is really “bloody stupid,” sort of like machine translations. Yet I remained concerned that, like bloody to some British minds, con might have retained its historic baseness, having derived, according to Le Petit Robert, from Latin cunnus, with the primary meaning, “the female sexual organs” – more precisely translated c-nt. But Robert adds that, “familiarly,” the word has meant “imbecile, idiot,” in the non-clinical, insulting sense, since at least 1790. Then, too, around the time I was struggling with this translation, a friend who had a master’s degree in French literature jokingly labelled something I’d said as con. She was a prim homemaker, and the third party in the conversation was a very intelligent if plain-spoken French teacher from Paris. I was hurt, but also the only one present who flinched. No one seemed to be calling me “the c word.” But the logomachy did not end there.

When I wrote about this private, possibly con, struggle in my column in The Lawyers Weekly, a reader assured me that, indeed, only “the vulgar” used con to indicate a stupid or idiotic individual. In a very nice note, it must be said, he explained that he had bachelor’s degrees from Lycée Mignet in Aix-en-Provence and Cambridge (in French), and a master’s degree in comparative literature. He had lived in France for two years, but admitted he hadn’t been there for twenty. Still, “I know for sure that con… means literally c-nt, and, I think, would not be used outside of a locker room by anyone of education, certainly not a judge in a court.” Which, as I say, was fair enough, and is a good indication that according to their sensibilities, age, geography, and experience, reasonable translators will differ.

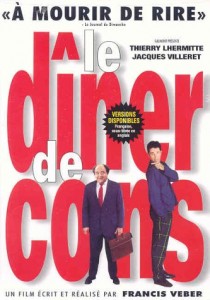

Indeed, three years earlier, the salient word – meaning “nitwit,” “nerd” in this case – was even featured in one of the year’s most popular films worldwide: Le dîner des cons (“The Dinner Game”). It was perhaps no answer to my anxious reader that the delightful (if nerdy) M. Pignon was the polar opposite of a c-nt, and that Georges Brassens (by then deceased) had been publicly performing what became the movie’s title song from about 1960, including this in the chorus(2):

Le temps ne fait rien à l’affaire. Time has nothing to do with it all.

Quand on est con, on est con! When you’re a con, you’re a con.

Qu’on ait 20 ans, qu’on soit grand-père Whether you’re twenty or an old grandpa,

Quand on est con, on est con! When you’re a con, you’re a con.

Entre vous plus de controverses, Enough of arguing again and again,

Cons caduques ou cons débutants. Clapped-out cons or rookie cons

Petits cons de la dernière averse Little cons of the latest rain,

Vieux cons des neiges d’antan. Old cons from the snows of yesteryear.

Not counting the repetition of the chorus, the word con occurs thirteen times in the song. Notice that, while I’ve tried to preserve the chorus’s rhyme scheme (more or less), I’ve left con untranslated, a choice I made given that I already have explained at length the various ambiguities at work. Again, it’s a matter of context, and, you, reader, now have sufficient information to make up your own mind about what Brassens means to say.

As a complete defence, at last, I rely absolutely on what M. A. Screech writes in his “A Note on the Translation” of his breathtaking rendering of Gargantua and Pantagruel (2006). As to “c-nt and con: conneries (“c-nteries”) is a word accepted in elegant French parliamentary debates or in a polished broadcast.”(3)

Notes

(1) Morning Star Co-Operative Society Ltd. v. Express Newspapers Ltd., [1979] F.S.R. 113. For a fuller discussion of this case, see my Where There’s Life, There’s Lawsuits: Not Altogether Serious Ruminations on Law and Life (Toronto: ECW Press, 2003). My working title for this book was, in fact, The Moron in a Hurry, but my publisher plumped (wisely, I now think) for a subheading in the manuscript, referring to trademark litigation by the Anheuser-Busch brewery, makers of Budweiser beer, over the slogan, “Where there’s life, there’s Bud.”

(2) From “Les trompettes de la renomée,” 1961.

(3) Rabelais, Gargantua and Pantagruel, trans. M.A. Screech (London: Penguin, 2006), xlv.

**If you’d like to be notified of each new posting, let me know via the “contact” page and I’ll put you on my e-mail list.**